Rapamycin (also called sirolimus) is one of the most well-known, researched, and promising drugs for anti-aging and longevity.

According to various experts, including Professor Matt Kaeberlein, it’s currently the best drug we have for longevity, significantly better than other drugs including much touted metformin (more about this drug later).

Rapamycin has been researched for decades by scientists all over the world, and numerous studies show that it can extend lifespan in various species (R,R,R,R), not only in diseased animals, but more importantly, also in normal, healthy animals (R,R,R).

Rapamycin, an immunosuppressive drug?

Many people believe that rapamycin causes too much immune suppression and increases the risk of infections.

The main rationale for this is that rapamycin is used as an immunosuppressive drug to prevent rejection of transplanted kidneys.

When organs like kidneys are transplanted, they are rejected by the immune system given transplanted kidneys look slightly different to the immune system than our own cells, causing the immune system to attack these foreign kidney cells and damage and reject the transplanted kidney.

Rapamcyin suppresses the immune system, so it won’t attack transplanted kidneys.

This is the main reason why many people think that rapamycin has strong immunosuppressive effects.

However, it’s not that straightforward. Many studies show that rapamycin can actually improve immune function.

So let’s get a closer look on how rapamycin can impact the immune system, negatively or positively.

Rapamycin in the context of kidney transplantation

A first important thing to note is that in the context of kidney transplantations, rapamycin is often given together with other, far stronger and more dangerous immune-suppressive drugs, like cyclosporine and corticosteroids.

The main immune suppressive effects come from these drugs. These drugs suppress the immune system not only far stronger than rapamycin, but they also have various more dangerous side effects compared to rapamycin.

For example, corticosteroids can lead to weight gain, skin bruising, thinning of the skin, metabolic problems, accumulation of abdominal fat, high blood pressure, muscle weakness, cataract and so on.

Second, in kidney transplant settings, rapamycin is mostly given in higher doses and continuously, meaning daily and without breaks. For longevity purposes however, rapamycin is often taken in lower doses: not daily, but weekly or every two weeks, while some longevity scientists recommend to regularly take “rapamycin breaks”, e.g. one takes rapamycin for three months with each time a 3 month break.

Third, we see that rapamycin could actually improve the immune system, both in a disease context and in a healthy context. Let us first discuss insights from animal studies before looking at human studies.

Rapamycin improving immune health in animals

Many animal studies demonstrate that rapamycin improves immune function, for example by increasing the amount of beneficial immune cells, or by increasing survival during infections.

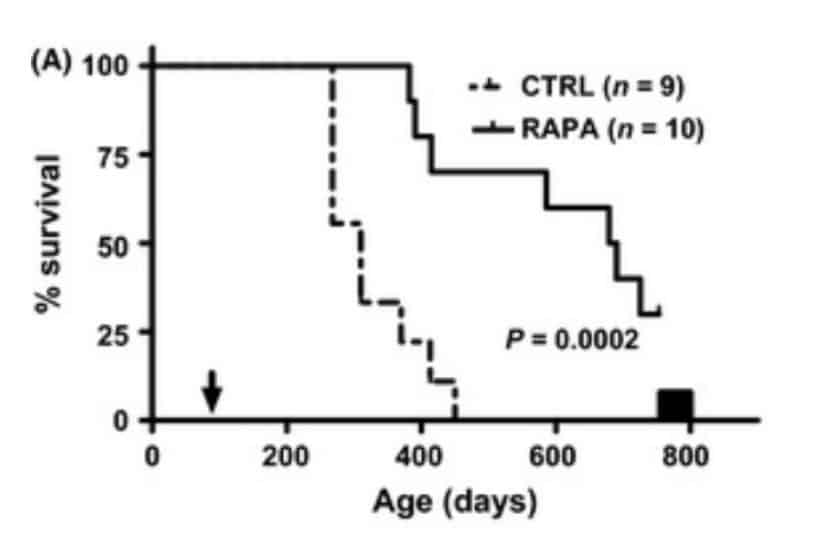

For example, in a study mice which were genetically modified to be immune deficient (RAG2 knockout mice, which lack T cells and B cells; these are important immune cells). These mice are very prone to infections and cancer (given immune cells are needed to attack cancer cells) and thus have significantly shortened lifespans. One would think that adding an “immunosuppressive drug” like rapamycin on top of this would even further impair immune function and reduce their lifespan by making them more prone to infections and cancer. However, in these mice, rapamycin actually significantly extended survival (R):

Severely immune-supressed mice that are given rapamycin actually live longer compared to control group mice.

Another study, which was a meta-analysis (a study that looks at many different studies at the same time), found that mice that got rapamycin actually had a reduced risk of dying from infections, while mice on dietary restriction had an increased risk of dying (R).

This is counterintuitive in two ways: first, dietary (or caloric) restriction is often touted as a way to slow down aging (at least in many different species) and to “rejuvenate” the immune system. But according to this study, caloric restriction increased the risk of dying from infectious disease (at least in rodents), while the “immunosuppressive drug” rapamycin reduced the risk of dying from infections.

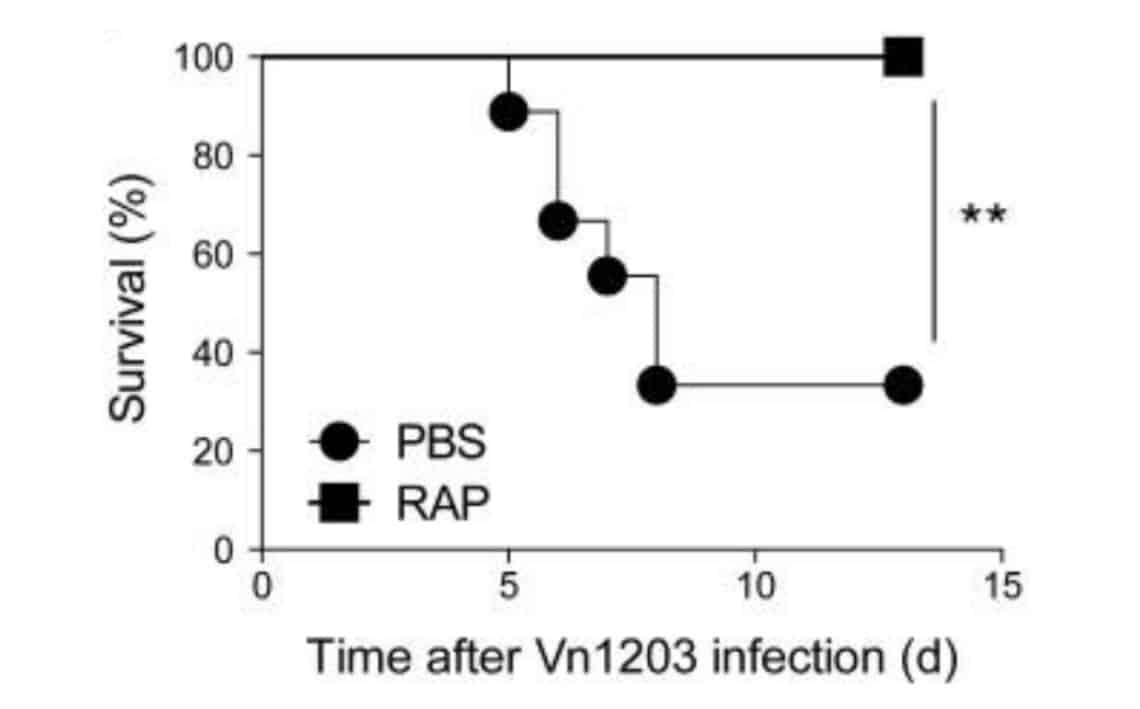

In another study, mice were injected with lethally high doses of the influenza virus. Only about 37% of the control group mice survived the infection, while 100% of the mice that got rapamycin were still alive (R):

Most mice receiving lethally high doses of influenza died, while the mice that received rapamycin all survived.

Many other studies show that rapamycin can improve immune function, increase vaccine efficacy, improve survival of infectious diseases and bolster antitumor immunity, among other things (R,R,R,R).

Other studies show that rapamycin could lead to immune system rejuvenation by improving hematopoietic stem cell function – these are the stem cells that create immune cells (R).

Rapamycin improving immune health in humans

In humans there are also many studies showing that rapamycin can improve immune function.

For example, when renal transplant patients are switched from cyclosporine (an immunosuppressive drug) to rapamycin, various diseases and problems caused by too much immunosuppression are reversed.

One such example of a disease that can arise due to too much immunosuppression is Kaposi sarcoma. This is a tumor likely caused by the herpes 8 virus that becomes unchecked when there is too much immunosuppression. This virus starts to multiply in the cells that line our lymphatic vessels and blood vessels, forming big purple lumps in the skin and other tissues.

It’s a dreaded complication in kidney transplant patients who take cyclosporine, given this drug allows free reign of the herpes 8 virus which induces and activates growth pathways in the cells it lives in (to increase its multiplication), leading to “uncontrolled” cell growth in the form of Kaposi sarcoma.

However, switching renal-transplant patients from cyclosporine to rapamycin resulted in all of the Kaposi sarcoma lesions disappearing in 100% of patients (R).

Rapamycin also improved the immune system in people with bladder cancer (R), and reduced the risk of cytomegalovirus (CMV) infection in organ transplant patients (R,R,R).

These are all things you would not expect from an “immunosuppressive” drug.

In healthy people, we see that rapamycin-like drugs can improve the immune system.

For example, in one study with 264 elderly people, a mixture of 2 mTOR inhibitors (called “rapalogues” – molecules similar to rapamycin) improved the immune system and reduced the rate of infections (R,R).

However, a later, larger study didn’t find a positive effect on the occurrence of respiratory tract infections (R).

This negative study got a lot of attention, given it was one of the first studies looking at a drug to “treat” aging, or at least a drug to improve an important aspect of aging, namely the aging-related decline in immune system in elderly people. If this trial would have been successful, it would be the first “longevity” drug approved by the FDA, in the sense that this could be a drug given to millions of elderly people to boost their aging immune system.

Unfortunately, this trial failed.

However, this should not really be that surprising. The study looked at the “number of infections” as a clinical outcome, which is a very difficult clinical endpoint, given so many things can impact the risk of becoming sick. For example, the amount of exposure to sunlight and vitamin D (an important vitamin for immune health), circulation of more viruses in specific groups or regions, stress levels, microbiome composition, medications people take, genetics, sleep deprivation, and many other factors can all impact your risk of becoming sick. One would need huge amounts of people to participate to try to account for all these potential confounders.

Furthermore, according to Dr. Joan Mannick, the leader of the trial, the Food and Drug Administration decided that the clinical endpoint (outcome) for this trial should be “respiratory infection symptoms” instead of “laboratory confirmed infections”. This approach could have confounded the study given that without lab test confirmations, one cannot properly differentiate between respiratory symptoms (such as a “cough”) caused by an infection or caused by non-infection related problems such as asthma, emphysema, heart problems leading to fluid build-up in the lungs and thus coughing, smoking, etc (R).

So it could be that in the non-rapalogue group (the control group) there were more people who had “symptoms of infections” (e.g. coughs), but perhaps these symptoms were not due to infections, but due to asthma, smoking, pollution, heart problems, and so on.

Rapamycin and immune health

Anyhow, to make a long story short, it’s interesting to see that many studies, done in humans and in animals, show that rapamycin can improve immune health.

This could help to somewhat allay the still very prevalent fear that rapamycin is a drug that suppresses the immune system and increases the risk of infections.

Dr. Verburgh will publish in a few months his new book;

likely the best book on longevity for the general public!

To stay updated, subscribe to our popular longevity newsletter!